- Home

- Tim Gallagher

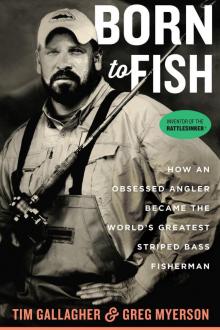

Born to Fish Page 9

Born to Fish Read online

Page 9

The three-way technique employs a three-way swivel tied at the end of the fishing line. One of the eyes of the swivel is attached to a couple of feet of leader with the hook and bait at the end. The third eye is attached to another leader with a heavy—three- to six-ounce—sinker at the end to pull the rig down to the bottom during a running tide. Greg honed and perfected the technique to fit his needs. He found that if he dropped his rig right down to the reef far below his boat and walked it slowly and gently along the rocks as the boat drifted, he could almost perfectly mimic the sound and behavior of a lobster, and thus attract the biggest bass. But could he catch them? Just because you lure them in with a strange noise doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll bite. Greg started hooking an eel on a short line a few inches from the rattle.

“I know as soon as they’re close enough to the rattle to hit it, they’re going to smell the eel, because they hunt by hearing first and then by smell,” said Greg. “The trick is to get them to think there’s a lobster in the area.” (Using a rattle sinker and eel is actually much better than even using a live lobster, which would be prohibitively expensive, only good for one or two drifts, and not as effective. A rattle sinker dangling a foot above the rocks sends out a better sound signal than a real lobster would, because it mimics the sound of a lobster moving through the rocks without being in the rocks.)

Greg didn’t stop there. He experimented with different kinds of fishing line and eventually changed from using monofilament, which most striper fishermen use, to a braided line.

“There’s a lot of stretch in monofilament, so you can’t detect the little hits made by stripers,” said Greg. “With the braided line, I can feel it even if a fish just swims past my line. Any little bump, and I know a fish is close by. A lot of times they hit the rattle sinker just because they don’t know what it is. And then they smell the eel.”

He also began working to develop a fishing rod that would be more sensitive and effective to use with his walking technique. First he shortened the rod and put a roller at the tip instead of the usual solid-metal guide. Braided line pulled taut by a big fish fighting to escape can be very abrasive to the metal guide at the rod tip, and a roller helps prevent excessive wear. Then he added more line guides to the rod, spacing them more closely. And he began using the old-style cork handles instead of the new foam plastic ones, because he found them more comfortable to use on a long night of fishing. (Years later, after he had caught the world-record striper, he designed a line of Greg Myerson signature rods for Lamiglas Fishing Rods, incorporating all of these design elements.)

One thing that has always fascinated Greg about the striped bass is that it has personality. It is very curious. Divers who have watched these and other fish underwater have noted the differences in the behavior of various species. Bluefish and many other fish species take off immediately if they see a diver. But a striped bass will come up and investigate to see what the diver is. Some researchers have been able to hand-feed large wild stripers, tossing out chunks of lobster to them.

“I use their curiosity to catch them,” said Greg. The sound made by his rattling sinkers piques their interest. They will sometimes smash into one of his sinkers or swim by quickly, swooshing past the fishing line. “I can almost predict exactly when they will hit the bait,” he said.

Greg’s invention worked better than he could ever have imagined. After he started using his crack-vial rattle sinker, he pulled out ahead of the other fishermen and never looked back. Fishing in ninety feet of water at night, in the dark, he was catching twelve stripers for each one the others caught.

“My sinker looked like everyone else’s except mine made a clicking noise,” he said. “And I started catching really, really big fish. It was my secret weapon.”

Before long, his friends stopped betting with him, so he started going out on big sport-fishing charter boats, the kind that can carry a hundred anglers. Most of the fishermen on the boats would put money in a betting pool, where the person who catches the biggest fish gets all the money. It became a big hustle for him. Greg won so often that people stopped putting money in the pool, or, in some cases, the captain of the boat wouldn’t let him compete in it.

This was when Greg truly honed his skills and fully developed the concept of the rattle sinker, from the time he was a college student and into his twenties after he left school. For years, he didn’t tell anyone how he was catching so many big fish—not until after he’d caught the world-record striped bass and decided to launch a company to manufacture and sell his invention to other anglers.

In addition to developing the rattle sinker, designing more effective rods, and improving striped bass fishing techniques, Greg studied the tides and the cycles of the moon—anything to give him an edge in his fishing. He noticed that the tides move very fast during new moons and full moons, making them a less desirable time to fish.

“At those times, the tide starts ripping so fast—three, four, or five knots [one knot equals 1.15 miles per hour]—you can’t even fish,” said Greg. “It’s not a good time for anything. A lobster can’t feed when the water’s rushing past at five knots.”

In Greg’s opinion, the best time to fish is during the first-quarter moon. “It’s a slow tide, with the moon dead high in the sky at sunset,” he said. “For a lot of the evening, the moon is right overhead, while the water is moving slowly and the lobsters are feeding. When the tide is changing, the water is almost completely still. You can almost fish the entire tide, and the water is never moving more than two knots.”

With all his years of experience in the waters of Long Island Sound, Greg could see how connected everything is in that vast ecosystem. As early as his late teens, he’d already been out there in every month, at all times of day and night, and in almost every possible weather condition, even when he had no business risking his life there. He knew the effects of the moon, the tide, and the seasons at an intuitive level, and he knew exactly when he’d have the best chance to catch the biggest fish.

* * *

Wild Man

Greg was living in a frat house made up mostly of football players. One Saturday night in early January, the frat house next door—where around a hundred students lived, most of whom disliked football players—was having a huge keg party. Its downstairs bar was packed with dozens of people, all drinking and partying. Greg’s frat house was fairly quiet by comparison, with fifteen or twenty people hanging around, drinking and smoking pot. Greg had already downed most of a bottle of Tanqueray gin and popped several codeine pills he’d stolen from the football trainer’s office. He was feeling no pain.

Tyrone, an African American student who was on the URI basketball team, showed up and said they should try to crash the party next door. Most of them didn’t want any part of it, but Greg was all in. He, Tyrone, and a couple others walked next door. A security guard stood at the entrance, while several large frat men were just inside, one of them drinking Jack Daniel’s from a bottle. Greg and his friends started to push their way inside.

“Hey, you can’t come in here,” said the guy with the whiskey bottle, and the guard and the other students standing nearby backed him up. Greg smirked and walked back outside. Determined to get into the party, he and Tyrone went around back to the fire escape, climbed up to the third story, and forced a door open. Greg took off his white ski jacket before walking downstairs, hoping no one would recognize him, but one of the men standing at the front door spotted him instantly. Grabbing Greg by the throat, he dragged him to the door. “Get out of here!” he yelled as he pushed him outside, but Greg got hold of the man’s collar and yanked as hard as he could, and they both fell off the porch into the snow. Greg was on him immediately, raining punches in his face. The man with the whiskey bottle, standing nearby, smashed the bottle right in Greg’s face, slashing his nose wide open. Greg didn’t feel anything. He stood up and landed a crushing blow to the man’s face, dropping him to the ground, and then everyone came surging out and lunging at h

im, trying to punch or kick him.

“Ten, twenty, thirty—I have no idea how many,” said Greg. “And they were all trying to get a piece of me. I was so stoned, I didn’t feel anything.”

Tyrone ran next door to get help, so Greg stood alone, facing a horde of angry frat boys. And he took them all on, throwing roundhouse kicks, swinging and punching, landing devastating blows. He finally made a break for it, trying to get back to his own frat house, but he was tackled in the parking lot. They were all kicking Greg as he lay there trying to cover himself from their attack.

“Hey, that’s enough,” said one of his attackers. “We’ll kill him if we don’t stop.” Then Greg got back on his feet and punched one of them in the face as hard as he could, and the whole thing started over, with everyone raining down punches and kicks on Greg and dragging him to the ground again.

The town police from Kingston, Rhode Island, finally showed up and separated everyone. Greg stood back up, his face bruised and bleeding profusely from his slashed nose, his shirt ripped to shreds. There was blood everywhere—his own as well as the blood of the people he’d hit. The police were holding back the crowd. “All right, all right, that’s enough,” they barked. “Everyone back off!”

Greg was in a strange daze. He barely knew what was going on around him, but he had no intention of quitting. He suddenly ran at the crowd full speed with his fist cocked up. “I remember seeing this one big guy’s face, and it’s like he’s thinking, ‘Holy shit! He’s going to hit me.’ And bang! I punched him in the mouth so hard he fell back ten steps.”

The crowd erupted instantly, shouting, “Kill him! Kill him!” and pushing through the police line. Greg made a break for it again and ran past his frat house, where all the football players lived. And everyone came running out, wearing football and hockey helmets, many of them carrying hockey sticks, lacrosse sticks, and whatever else they could grab. A huge brawl ensued, and the police couldn’t stop it.

As the fight went on all around him, Greg was lying over a sewer grate, listening to the sound of his blood dripping down into the water. His friends finally picked him up off the ground and took him to the student infirmary. The place was overwhelmed as a dozen or more badly beaten students showed up, one after another. Some of them, including Greg, needed surgery. Ambulances arrived and took the most seriously injured students to nearby South County Hospital. The emergency room looked like a disaster zone, with bruised and bleeding frat boys on every available bed or gurney. Greg was on a table getting stitches in his nose. The guy on the next table was the one he had run over to and smashed in the mouth as the police held everyone back. Both his upper and lower lips were split open and a surgeon was sewing them up. The guy turned to Greg and said, “What the fuck did you do this to me for?”

“Well, you shouldn’t have been outside, you fat fuck!” said Greg.

“You’re dead, Myerson. You’re fucking dead!”

Greg broke away from the doctor who was sewing him up and started punching the other man in the face until his stitches opened up and his lips were bleeding profusely again. The state police came rushing into the emergency room and put handcuffs on Greg, which he wore through the rest of his surgery.

The fight was covered in both the Providence Journal and the student newspaper, The Cigar. The headline read: “Greek Misunderstanding Sends 10 to the Hospital.”

After the night of the brawl, people at URI viewed Greg differently, and no one wanted to mess with him. “I was well known on campus, and feared after that by everyone,” said Greg. “I wasn’t a bad dude, I just wouldn’t take any kind of crap.”

The police and the campus blamed Greg for the brawl, and he was put on probation at the university. As punishment, the director of Campus Life required him to drive the handicapped van around campus, but Greg came to enjoy spending time with the students he drove.

“There were all these students in wheelchairs—paraplegics—and I would visit them in their dorm rooms,” said Greg. “They loved me because I’d come walking in with football players, and we’d smoke weed with them and bring them to places with us. We became friends. They were good people.”

Greg’s time at the University of Rhode Island did not end the way he had hoped, with a bachelor’s degree and a spot on an NFL team. He was an amazing football player, as anyone who ever saw him on the field can attest, but the academics—and the drugs and alcohol—did him in. His heart was just never in it, and at the end of his sophomore year of college, he was on the ropes. Late in that second year he tried to turn it around. He managed to get his grades up in a couple of classes, but he needed one professor to give him an incomplete instead of an F to be able to keep his athletic scholarship. He explained the situation to the professor and said that he’d had three surgeries on his nose that semester (thanks to the brawl) and had gotten behind in his work.

“You should have come to me earlier,” he told Greg. “There’s nothing I can do now. But if you get an A on your final, you’ll pass the course.”

Greg knew there was no way he could ever get an A on his exam, so he implored the professor to reconsider. “Look, I really need this incomplete.”

“Maybe you should just go home and bag groceries for a while and figure out what you want to do with your life,” he said.

“I wanted to kill that guy,” said Greg. “But he was right. I didn’t know what I wanted. I was at URI for two years, and then it was over, along with any chance I had of ever playing in the NFL.”

* * *

Rasta Mon

Greg was at loose ends when he left the University of Rhode Island. He couldn’t stand being stuck at his parents’ condo. His father was sicker than ever and kept begging Greg to put him out of his misery; and his mother was furious with him for dropping out of college and scolded him constantly. “Why can’t you be more like Dave?” she fumed. Even when she didn’t say anything, Greg knew exactly what she was thinking, and it made being there a nightmare.

He drove his Jeep to a vegetable farm not far from home to try to get a job. With his background in the vo-ag program at Lyman Hall High School and his previous work on farms, he was an instant hire. He worked alongside nearly two dozen Jamaicans, who would come to this area for a few months each year as migrant farm laborers, then go back home with the money they’d earned. The wages were much better in the United States than what they could earn in Jamaica, and many farm owners considered them the most skilled, efficient, and hardworking farm help they could find anywhere.

Greg was a hard worker and was put in charge of one of the two crews of ten Jamaicans. The Jamaicans loved Greg, because they knew he respected them. He had been growing marijuana at home in his closet, using a grow light, and he had a good-sized stash of it. He would bring a bag of it each day to share with them, and they would smoke it together whenever they took a break. The other crew didn’t get to do this. For the Jamaicans, this fit right in with their lifestyle at home, and they worked all the harder for Greg. He was the perfect boss man for them. Their output was amazing; they were picking nearly twice as much as the other crew.

Greg enjoyed working with the Jamaicans. He admired their easygoing worldview; nothing fazed them. They were so close-knit, friendly, and generous—and they had such a great dialect. Greg was soon speaking just like them, which endeared him to them even more.

One of Greg’s favorite workers at the orchard was Winston, a stocky, six-foot-five, middle-aged Jamaican whom the others on the crew called the “Long Man.” At the end of the harvest, when the last of the crops had been picked, Winston invited Greg to come and visit him at his home in the mountains of Jamaica, and Greg said he definitely would. He started making arrangements, getting a passport and a one-way ticket to Kingston, the capital city of Jamaica. Greg wasn’t sure how long he was going to stay, perhaps only a week or two, but he figured he could just buy a return ticket whenever he decided to come home.

Greg arrived at Kingston airport with the clothes on his back, $3

00 in his pocket, and a backpack with a few additional items of clothing. He had only a vague idea of where he was going. Winston had told him to get a cab and tell the driver to take him to an area in the mountains, about twenty miles from Kingston, and ask around for him. He followed Winston’s instructions, but the cab driver seemed shocked when Greg told him where he was going. “Why you wanna go there, mon?” he asked, gazing quizzically at him in the rearview mirror. But he went ahead and drove him there. As they got higher into the mountains, the road became ever more treacherous—muddy and washed out in places. The driver finally said he could go no farther in his battered old Ford station wagon. So he pointed the way to Greg, collected his fare, and wished him well.

Greg still had five or six miles to go, but he had a strange sensation he was being followed. He kept catching glimpses of a couple of men walking behind him, but whenever he looked back toward them, they would duck quickly into the trees and undergrowth and hide. Then he didn’t see them for a while, until suddenly they jumped out ahead of him in the trail, wielding machetes threateningly. Somehow they had made their way around him through the woods and gotten out in front. They took his backpack, which contained his passport and other identification, his clothes, and all of his money. They even took his shoes and the shirt off his back. Greg was barefoot and clad only in cutoff shorts when he found Winston a couple of hours later. The Long Man welcomed him warmly, laughing heartily and hugging him like a long-lost brother.

Winston lived in a small two-bedroom wooden house—just a shack, really, like something from the 1960s television show Gilligan’s Island, cobbled together from various planks, two-by-fours, and other building materials he’d acquired over the years. Winston was considered better off than most of the other people in the village because of the farm work he did each year in the United States, but his house was little more than a hovel. Still, Greg was happy to have a room of his own in such a beautiful place.

Born to Fish

Born to Fish