- Home

- Tim Gallagher

Born to Fish Page 20

Born to Fish Read online

Page 20

“Absolutely, man. We’ll have fun with it.”

As soon as Greg walked back through the double doors, Al and Mike jumped on him. “They were all pumped up,” said Greg. “They came running in and jumped up. They’re both tiny guys, and I actually caught one of them.” They took him to see the psychiatrist who decompresses everyone who appears on the show. She asked Greg if he felt humiliated. “Fuck no!” he told her. “I just got a deal with Mark Cuban.”

* * *

The Pendulum Swings

As I sped through the second red light, I glanced over at Greg, riding in the passenger seat, his head leaning against the side window. Although it was late in the evening and dark, the streetlights at the intersection lit up the inside of my truck, and for an instant I could see how pale he looked. He was barely conscious. I should’ve called a damn ambulance, I cursed under my breath, then looked away and drove faster, desperately racing to Yale–New Haven Hospital, still nearly ten miles away.

I felt so stupid. I should have brought him there two or three hours earlier, when we first gave up our plans to spend all night fishing on Long Island Sound. We both knew the fishing would be great that night, with numerous huge stripers passing through off Block Island, where we planned to go. I should have realized that Greg would have had to be on death’s door to pass up the chance to go out and catch some of them. He’d had a major flare-up of ulcerative colitis, which had plagued him on and off for several years, and had been self-medicating with the powerful steroid prednisone for a couple of weeks, to treat severe inflammation and internal bleeding. It had always worked for him in the past, but somehow this time was different. He was only getting sicker. On the drive back from Westbrook Harbor, we’d had to stop at a gas station so Greg could use the restroom, and he had nearly filled the toilet bowl with blood. When we finally got to his house, I asked him if he needed to go to the emergency room.

“No, I just need to get some rest,” Greg told me. “Let’s just wait until morning. If I’m still in bad shape, I’ll go to the hospital.”

“Are you sure?” I asked. He nodded and walked to his bedroom. “Okay,” I said, as I started unrolling my sleeping bag on the couch in his living room. But I didn’t feel good about it. Greg looked terrible. He had been sweating profusely and shivering, obviously burning up with fever and in a lot of pain. Awful thoughts kept nagging at me: What if he doesn’t make it until morning? What if he bleeds to death as I’m dithering around, trying to figure out what to do? Maybe I should call an ambulance. I was filled with indecision. I finally couldn’t take it any longer. I went into Greg’s room, where he lay sprawled across the bed with his clothes still on, and told him, “Get in the car. We’re going to the hospital.”

A minute later, we were on our way, speeding to New Haven, nearly fifteen miles away. But had we waited too long? It seemed obvious to me now that Greg was in imminent danger of dying. Why hadn’t I done something sooner? He was bleeding out inside and only a hospital could help him, if I could just get him there in time.

As we finally pulled in at the emergency room door, I parked illegally along the curb and ran inside looking for someone to help him. By then, Greg could barely walk. I must have looked terror-stricken as I babbled on about my friend who was bleeding to death in my car outside. An emergency room staffer quickly brought out a wheelchair and whisked Greg away to see a doctor, while the other patients ahead of us still sat in the waiting room.

I stayed at the hospital for a good part of the night as the medical staff gave Greg a blood transfusion and stabilized him. A couple of hours later, Greg seemed much improved. The transfusion and the pain medication had done wonders. The color had returned to his face and he was sitting up in bed, but he still seemed very weak. Now that the life-and-death situation had passed—or at least been put on hold—the doctor took the opportunity to let Greg know how appalled he was that he had waited so long to be treated. He should have come in at least two or three weeks earlier, he grumbled, and it was truly amazing he had survived at all. Greg nodded and looked away. Then a nurse standing nearby, who kept peering intently at Greg, said he looked very familiar. Greg mentioned he’d been on Shark Tank recently, and the nurse’s and doctor’s faces instantly lit up. “I saw you on that show!” said the doctor, gleefully. “The fisherman!” And suddenly the old Greg was back, his face beaming as he started spinning hilarious yarns about Shark Tank and his bantering with Mark Cuban and the others. He had everyone in the room laughing, including a couple more nurses who had heard the laughter and come to investigate. Once again, he was in his element with an audience of eager listeners. I knew right then that he was on the road to recovery and it was safe to leave.

I excused myself and told Greg I’d be back in the morning. As I walked through the hospital corridors, trying to find my way out, I could still hear peals of laughter coming from Greg’s room. Thankfully, my truck had not been towed away, so I climbed inside and drove back to Greg’s house in the darkness.

The next morning when I came to visit him, Greg said that the doctor had told him he was sure he would not have lived until morning if he had not come to the emergency room the night before. “You know, you saved my life,” he told me, then smiled. “I don’t know how many more lives I’ve got left; I’m definitely way past nine lives.” We both laughed. I was so relieved that everything had worked out. For a while, during the last few miles before we got to the hospital, his survival seemed anything but certain to me.

I left for home the following day. The doctors kept Greg in the hospital for ten days before they dared to release him, no doubt fearing he might have a sudden relapse of the dangerous bleeding and wanting to monitor him closely as they worked to stabilize his condition. His internal swelling was so bad that the hospital couldn’t perform a colonoscopy to see exactly what was going on. But they were trying a different medication, which seemed to be improving his condition.

As I drove home to Central New York, I thought about Greg’s life and what a wild ride he’d had. I know that everyone’s life is like a pendulum, with numerous highs and lows between the cradle and the grave. But with Greg, the swings of the pendulum are so much more extreme than with anyone else I know, casting him from the lofty heights of his Shark Tank appearance, when he won over the hard-nosed Sharks as well as a national television audience, to this near-death experience a few months later. Of course, the seeds of this downturn were actually sown during the run-up to his Shark Tank appearance, when his stress level went through the roof for weeks as he pondered the possibility that he might make a fool of himself on national television, and he was also terrified about flying to Los Angeles and back. His colitis had returned with a vengeance at that time and never really abated. But I felt strongly that Greg’s pendulum would soon swing upward again to heights he’d never yet seen. It didn’t take long.

A short time after he recovered, Greg met Mark Freedman at a charity fishing tournament in New York City. Freedman was very taken with Greg’s charisma and fascinating backstory. “I thought, This guy is so colorful, he deserves a shot at doing some kind of TV show,” he told me—and Freedman is just the person who could make that happen. As a film and television producer and licensing agent (and founder and president of Surge Licensing), he is a star-maker of the first magnitude. It was Freedman who “discovered” a little-known cult comic book called Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and turned it into a billion-dollar franchise, spinning off popular movies, television shows, live events, video games, and various merchandise. He has also produced outdoor television programs, most notably The Best and Worst of Tred Barta, which ran for nearly a decade on cable television—and featured another charismatic, one-of-a-kind outdoorsman.

Freedman has been brainstorming with Bob Wheeler (of Wheeler Communications)—the producer/director he teamed up with on Tred Barta’s show—to develop a concept for a reality television show featuring Greg. Most fishing shows currently on cable television are “time buys”—that is, the

producers buy a particular time slot from a cable network and have to fund it themselves or through a large advertiser. The shows often end up being essentially a thirty-minute advertisement for a product or company. But Freedman and Wheeler have much larger ambitions for this project. They want to create an original series—in which case the television network or streaming service would pay for the show. And they want it to be much more than just a fishing show.

“I don’t want to have what I call a ‘bent rod’ show, catching big fish on every episode,” said Freedman. “There are just so many times you can shout Ooh! and Ah! and Wow! It gets boring really fast. I’m looking to broaden this out and have it appeal to a general audience—attracting the outdoor fisherman and hunter but also drawing in people from other walks of life, who’ll say, ‘Wow, this is cool. I really like this guy and the people he surrounds himself with.’”

Freedman and Wheeler got a taste of what this show could be last May when they dropped in on Greg and his crew at the World Record Striper Company headquarters—Greg’s basement—and spent a couple of days doing preliminary filming. (Wheeler had come all the way from Atlanta.) They took a shotgun approach—no plans, no script, just shooting tons of video of whatever took place. Several of Greg’s friends were there—Matt, who was with him when he caught the world-record striper; Bill, an old friend from his high school football team who had lived with him in the condo at Lake Tahoe; Jeff, the captain of the World Record Striper Company charter boat; another Jeff who often crews on the boat; and a guy everyone called The Vegetable, whom Greg had known since his Little League days. The Vegetable, or “Veggie” for short, bears a striking resemblance to Kramer on the TV show Seinfeld, with a shock of wild, blown-back hair and a manic quality that brings a jolt of high energy to the shop—energy that unfortunately doesn’t seem to transfer into productivity. Everyone sat in folding chairs at an old poker table—the same table Herb and his mob associates had sat around some forty years earlier.

They were ostensibly filling orders, bagging up RattleSinkers, putting them in Priority Mail boxes, and sending them to people who had bought them through the company website. But there was constant laughter, bickering, teasing, and food breaks—the infectious chaos of Greg’s day-to-day existence—so very little work was accomplished. It started out when Bill brought a kosher breakfast of lox and bagels for everyone, and they spent an hour munching on the food, talking, and laughing.

Freedman and Wheeler stepped outside briefly to talk privately but were overheard. “Every time I’ve been here it’s like this,” said Freedman, laughing. “This is the way these guys really are. None of this is staged. This is the way the company runs. It’s great!” Wheeler nodded enthusiastically and laughed.

A short time later, Ralph D’Arco of Radfish Lures, who is working with Greg on a new line of freshwater jigs for catching largemouth bass, showed up. He had driven down from Springfield, Massachusetts, and brought the crew a bunch of Italian food—calzones, sausage, meatballs, and even cannolis—so they started scarfing it down instead of working. And then Greg’s girlfriend, Mary, a fitness trainer, walked in just as he was filling his face. She exploded. “What are you doing?” she said angrily. “We were supposed to go walking.” She had been urging him to lose weight and get in better shape. “If you’re not going to take this seriously then I’m not going to waste my time!” Wheeler just kept right on shooting video through their whole exchange. And when the two of them finally left to take their walk, he went along and filmed it. Mary was as good on camera as Greg was, and the chemistry between them was electrifying.

Later that afternoon, Greg went out fishing, taking Freedman and Wheeler and a few other people, even though a howling gale was whipping across the water. It was hopeless to try to go out into Long Island Sound, but Greg managed to catch several stripers in the Connecticut River. It was a crazy time, but by then Freedman and Wheeler were ecstatic about the possibilities for a TV show. They were very happy when they left the next day.

I had a long talk with Freedman later. To him, Greg is far more than just a fisherman. He has many different sides. “He’s charismatic, there’s no question,” he told me. “He’s very comfortable in his skin. You could see on Shark Tank, he just exudes confidence. And people really like him.”

Freedman envisions the show being like a cross between the reality show Duck Dynasty and the popular 1980s and ’90s NBC sitcom Cheers—only instead of being set in a fictional bar populated with colorful characters who come together to drink and banter with each other, the action in this show would take place in a fishing-tackle shop with Greg and his fishermen friends, who drop in to visit or help him with his work.

“I see the World Record Striper Company as Greg’s headquarters . . . his base where all of his friends show up,” said Freedman. “If you’re a fisherman, a bait and tackle shop is a place you go to hang out, BS, buy some equipment, or just be around a community of fishermen, which are an interesting breed unto themselves.”

Freedman should know: he’s been an avid fisherman himself for years and spends countless hours fishing for striped bass on his boat or from the shore near his home on Long Island. “Fishing is a disease,” he said, laughing. “Once you get hooked, it grabs you. It’s very addictive. These guys sacrifice everything to pursue fish. That’s why they’re not married, or can’t stay married, because when nature creates these moments when the fish are moving through, they just have to go after them.”

He has nothing but admiration for Greg’s skills as a fisherman. “He has almost this sixth sense—he really thinks like a fish. I consider myself a very good fisherman, but Greg is the real deal.”

Freedman also likes the fact that Greg is encouraging anglers to practice catch-and-release with striped bass. “The striped bass is an absolutely adored fish—one of the most important recreational fish around,” he said. “But not everyone understands the importance of releasing them. They don’t understand the ecological side of it. Everyone says to me, ‘Don’t you want to bring home dinner?’ And I say, ‘No; striped bass are much too valuable to catch just once.’”

So where does this all go from here? The next step will be to do more videotaping when the stripers are here in large numbers this summer and create a pilot to shop around to television networks. If Greg’s pendulum swings higher still, he may soon begin a new phase of his life—as a television celebrity.

Epilogue

September 16, 2017. Brewer Pilots Point Marina, Westbrook, Connecticut. The Fishing for Cancer Tournament is finally over, the barbecue has begun, and the awards for the biggest fish will soon be handed out—but not to our team. All of the huge fish—with the exception of some good-sized bluefish we caught this morning—eluded our team. But we were winners in other ways: we had raised the most money for the charity and the tournament was catch-and-release. It was originally going to be a kill tournament, but Greg insisted he would not lend his name to it or participate in any way unless it was strictly catch-and-release. Thanks to him, every single one of the striped bass caught in the tournament was still alive.

At the captains’ meeting the previous evening, each team was given an official peel-and-stick measuring tape to paste down on the decks of our boats in a place where a fish could be quickly laid down next to it and photographed to establish its length. The tournament rules required three photos of each potential winning fish: one of the angler holding the fish, one of the fish lying next to the measuring tape, and one as the fish was being released alive.

Greg encouraged everyone to send an email message from their smartphones, with photos of a potential winning fish attached, to the headquarters as soon as possible after releasing the fish, so other anglers would immediately know the size of the top contender at any given time. If the biggest fish caught so far was, say, 45 inches, the bar was set, and everyone would know that they could release anything smaller without subjecting the fish to any unnecessary additional stress just to take pictures.

&nb

sp; At the end of the meeting, everyone had headed out, hoping to catch a bigger striped bass or bluefish than anyone else. The sun was just dipping below the horizon as we entered Long Island Sound. The remnants of Hurricane Jose still lingered along the East Coast, creating huge swells and wild surf, but we barely felt it in the shelter of the sound as we blasted across the water with the throttle down, salt spray exploding over us. Greg had decided to take our boat all the way to Montauk Point, nearly thirty miles away at the easternmost tip of Long Island. Of course, it was a gamble. Montauk could be hit or miss this time of year. If the stripers are moving through in decent numbers it could be truly great—or not, if they were absent. The latter was the case that night for our boat and all the others working the waters off Montauk.

Walter Anderson and his teammates, Keith Salisbury and Ed Noble, had a much better time. They had decided to stay close to shore that evening, fishing along the Connecticut coast, and got into some stripers within fifteen minutes of leaving the marina. At one point, all three of them had fish on at the same time. When Keith landed a 46-incher, Walter took the necessary photographs and emailed them to the Fishing for Cancer headquarters. “Greg thought there was a good chance my boat would catch the first fish,” said Walter. “He said to me, ‘Look, if you catch a good fish early, set the bar. That’ll save a lot of fish from getting manhandled.’ ”

On our boat, when we saw the photo, we immediately knew things were not shaping up well for us. Greg laughed and took it all in stride. At another time in his life, he might have raced back to the Connecticut coast and spent the entire night working the water, determined to get the biggest bass, but his outlook had definitely matured. We continued to fish where we were for a few more hours, then we tied up in Montauk and slept on the boat. The next morning, we caught a few bluefish on the way back before calling it quits around noon, ending the tournament in good spirits.

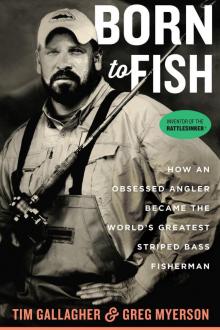

Born to Fish

Born to Fish