- Home

- Tim Gallagher

Born to Fish Page 2

Born to Fish Read online

Page 2

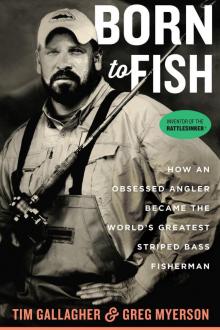

One of the things about Greg Myerson that interested me most when I first met him six years ago was his deep concern for the fish he was catching. Here he had worked his entire life to become the top striped bass fisherman in the world, and just when he achieved this crowning goal, he had misgivings. He decided to step back from what he was doing and think about what was best for the striped bass themselves. Although he still fishes almost every day of bass season, he has turned away from killing big bass and wants no part anymore in tournaments that kill them. Greg is now actively promoting catch-and-release tournaments. On his Facebook page, he often states how long it has been since he caused the death of a striped bass—currently more than three years.

You may well wonder where a person like Greg Myerson came from: what factors in his background came together to produce such a competent and thoroughly obsessive angler. This is what I hope to provide in the pages of this book, an intimate look at the making of a world-champion fisherman—a man who was born to fish.

* * *

Born to Fish

Herb Myerson could not have been more different from his son Greg. Although they were both strong and athletic, Herb had always been a city boy. Raised in Brooklyn, he’d never known any other life but the dense urban sprawl of New York, whereas from his earliest days, Greg loved nature and being out in the country.

Everybody loved Herb. Outgoing and charismatic, he stood six foot three and weighed 260 pounds, but he was lithe and graceful and enjoyed dancing. Tanned, handsome, and muscular, with thick, jet-black hair, he had once modeled shirts for magazine ads. But that wasn’t surprising: he came from a family of good-looking people. Herb’s aunt was Bess Myerson, who had won the Miss America pageant in 1945 and been a popular television personality in the 1950s and ’60s.

Herb was a Vietnam vet and had moved into his parents’ apartment in Hamden, Connecticut, when he first returned from the war. It was there, at a party, that he met Diane, a beautiful young widow who lived in the same building with her one-year-old son, David. Her husband had become seriously ill and passed away a short time earlier. She and Herb were immediately drawn to each other and made a striking couple. They often went dancing and also loved to go bowling. But the two had very different temperaments. Herb was the picture of cool. Beyond unflappable, nothing got to him, but his calm could be frightening at times. Diane was the opposite, volatile and emotional, always ready to explode. But they soon got married, and a couple of years later, Greg was born.

Herb adopted David and made him a Myerson. Neither Greg nor David knew they were half brothers until they were grown up. They had no reason to wonder. They looked alike—tall, strong, and athletic—and spoke in a similar way. And Herb and the rest of his family treated the two boys exactly the same. There was never any favoritism. Herb was the only father Dave ever knew, and Herb completely embraced him.

The Myerson family had an interesting religious mix—Diane was from a devout Polish Catholic family, and Herb’s family was Jewish. They observed the important sacred holidays of both faiths, celebrating Christmas and Hanukkah, Easter and Passover. Although Herb was more of a secular Jew, his father was devout, regularly attending synagogue and making sure Greg and Dave observed Hanukkah and other major religious events in the Jewish calendar.

Greg was only a toddler when his family moved from their apartment in downtown Hamden into a Colonial-style house they had built in a rural area, with woods and farmland, near North Haven, which proved an ideal home for Greg and Dave. From the start, Greg lived to be outdoors, close to nature. He had no interest in the pursuits of his family and most other people his age.

Herb and Diane never understood Greg’s ways—his constant need to be roaming the woods and fields and streams near their home. They knew only urban life. But Greg was a remarkable child who followed his own path from his earliest days. And he was always obsessed with fishing. Even as a two-year-old, he would stand for hours with his toy fishing rod, dangling a plastic fishhook into the muddy water of the drainage ditch in front of his house. Aunt Cookie, Diane’s youngest sister, told me no one could drag him away from that ditch.

“He would sit there for hours every day, loving it,” she said. Later he started building dams with stones in the tiny stream that flowed through his backyard, and he’d catch the little fish he found there, mostly shiners.

“I was always there,” said Greg. “I loved it.”

Greg was like a latter-day Huck Finn—but where did that come from? He seemed like such an anomaly in his family and in the town where he grew up. His high school football coach, Phil Ottochian, perhaps put it best: “He was born in the wrong century,” he told me, laughing. “He should have been a pioneer—The Plainsman.”

Where Greg got his obsession with fishing, nobody knows. His parents certainly didn’t encourage it. They had no interest in field sports or any kind of nature-related activities. But he did get some encouragement from outside his immediate family. His grandmother’s backyard was right on the Muddy River in North Haven, and his Aunt Cookie was always fascinated by Greg’s overpowering interest in fishing. She recalls sitting with her mother on lawn chairs at the edge of the river and watching young Greg trying to fish as a four-year-old. His preoccupation with fishing was good for Cookie and her mother because it gave them time to talk with each other instead of spending all their time looking after Greg. One day, Greg was getting discouraged because he hadn’t gotten any bites. “You just need to keep trying, Gregory,” said his grandmother. “It takes a lot of patience to catch a fish.” Another two hours passed, still with no action. He finally dropped his rod to the ground. “I don’t think there’s any fishies in here, Grammy,” he told her.

Greg’s mother always had to insist that Greg be allowed to take a fishing rod to various summer camps or on vacation with them or he would refuse to go. Going to Florida as a kid, he wouldn’t even get in the car unless they either brought a fishing rod or promised that his Uncle Donny would have one for him when they got there.

“A fishing rod has been a part of me, like an attachment to my body, for most of my life,” said Greg. “When I was a kid, walking up and down the streets, I always had one.”

Seymour Myerson, Greg’s grandfather, encouraged his interest in fishing. A big, good-looking man much like his son Herb, Seymour was also very good-natured; he enjoyed spending time with Greg. Although he knew nothing about fishing himself—his only connection to it was that he had once worked in the Fulton Fish Market in Brooklyn—he could see Greg loved it, so he started looking for places to take him. When Greg was still in nursery school, but already a decent young angler, Seymour found a place called Corey’s Fish Farm not far from Greg’s house, and he started taking him there whenever he came to visit. It was one of those places where you pay by the pound for any trout you catch, and some of them were good sized. The place had three ponds—two were about a half-acre in size and the other was more of a lake—with a shack in between. The smaller ponds each had a huge fountain in the middle, shooting water high in the air, to keep it aerated. Corey lived in the shack and had big mounted trout hanging on the walls.

“I loved that place,” said Greg. “I would stare at those mounted trout like they were the greatest things in the world—and to me, they were.”

He would stand at the edge of the pond for hours, casting his baited hook as far as he could. Mr. Corey took a liking to Greg and showed him how to fish more effectively for the trout—by forming trout meal into a ball around the fishhook. This was what they fed the trout every day, so it was amazingly effective.

“After a while, I became a regular at Corey’s, and he didn’t charge me to fish,” said Greg. “I would help out, feeding the fish and cleaning up.” He and Corey would talk for hours about trout. And Greg loved bringing home the fish he caught to his family. He would also take trout to his nursery school teacher. Greg always insisted on giving trout to Seymour, who didn’t really like to eat fish but took them anyway to avoid

upsetting Greg, thanking him profusely and then tossing them out his car window into the woods a half-mile down the road. (One day a policeman saw him do this and pulled him over for littering. But he had to laugh when Seymour explained the situation, and he let him go with a warning.)

Before he was even kindergarten age, Greg had his first close brush with death after being stung repeatedly by a swarm of yellow jackets. He’d stirred up the wasps by poking a hockey stick into their underground nest. He had an intense allergic reaction to the stings and went into anaphylactic shock. (Before this, no one had known he was allergic to the stings of bees, wasps, and hornets.) Within seconds, he fell to the ground, barely able to breathe. He managed to crawl into the kitchen and collapsed in front of his mother, who was having coffee with a neighbor. In a panic, his mother called the paramedics, and shortly after they arrived, an ambulance rushed him to the nearest hospital. Greg remembers being put on a stretcher and looking up at the paramedics as they ran toward the ambulance and rushed him inside, his mind hovering at the edge of unconsciousness. He didn’t feel fear at this point, but almost a sense of fascination with the rapid events unfolding around him as he lay dazed and fading on the stretcher.

For the paramedics, it was a frantic race. Greg needed equipment that only the hospital had to keep him breathing and stabilize him. His lungs had collapsed by the time he entered the emergency room; his condition was so grave that a priest was brought in to administer last rites. By then, Greg had already slipped into a coma. When he finally awoke days later, most of Greg’s family were gathered in his hospital room. Seymour stood next to his bed, smiling broadly and tearfully as Greg opened his eyes. The sense of relief Seymour, Herb, and Diane felt when Greg awoke, after days of languishing in a coma, was so profound they all burst out laughing.

“I remember waking up and seeing my grandfather standing there laughing,” said Greg. “They were all laughing.”

GREG’S MOTHER taught history at Norwalk High School, having earned her master’s degree at Quinnipiac College. Diane always pushed her sons academically, determined that they would be successful and lead meaningful lives. But her pushiness irked Greg from a very young age. Although he was always a bright child, he was dyslexic, so reading did not come easily to him.

“My mother and I really never got along,” said Greg. “She was always preaching at me, trying to teach me things. We would butt heads all the time; I never wanted to listen to her.”

Greg began staying frequently at Diane’s mother’s home. She lived in a tiny house with her ninety-nine-year-old father, right on the banks of the Muddy River, about four miles away. Quiet and self-effacing, she was nothing like Diane, and Greg loved to spend time with her.

Greg’s great-grandfather, who spoke only Polish, had his own room in the house. He and his relatives had come to America in the heyday of Ellis Island, when thousands of immigrants flooded into the United States. The family brought a strong work ethic and a need to lead purposeful lives, ever pushing to improve their lot. They had bought a huge house in New Haven early in the twentieth century, and all of their relatives who moved to America would live in it until they got on their feet and could afford their own homes. Theirs was a culture of always striving to improve, to become the best you could hope to be. This is the ethic Diane had inherited and perhaps the reason she often seemed unbearably pushy, especially to Greg, causing him to flee to her mother’s home so often.

Greg would spend hours there watching Red Sox games on television with his great-grandfather, who would always wear a Red Sox cap and smoke his pipe. “Just about the only word he said that I recognized was ‘Yastrzemski,’ ” said Greg, laughing. “He’d say, ‘Yastrzemski go three round!’ which meant Carl Yastrzemski had just hit a triple.” After his great-grandfather died, Greg moved into his room and lived with his grandmother for months. She was a devout Catholic and would pray the rosary each morning when it was quiet. “I would sit there on the couch and do it with her,” said Greg. “I loved it.”

When Greg was six years old, the family went to visit his father’s relatives in Florida. His Uncle Donny owned a textile factory there and had a sport-fishing boat he kept at a yacht club in the Florida Keys. One day they were having a big party on the boat and everyone was drinking cocktails and eating shrimp. As always, Greg had brought a fishing rod with him, so he grabbed a few shrimp to use as bait and walked down to the end of the dock. After baiting his hook, he cast it out into the water and began reeling in. Then he spotted a huge barracuda, nearly six feet long, and cast the shrimp right in front of it. The barracuda attacked instantly, grabbing the shrimp with a huge splash. It took off so fast and powerfully, it ripped the rod right out of Greg’s hands, and he fell off the end of the dock. He panicked, splashing and crying until his uncle and parents came running up and rescued him.

“What the hell happened?” asked Uncle Donny.

“A big long fish took my rod,” said Greg. His uncle quickly hired a diver to go under the dock and retrieve the lost fishing rod.

“My Uncle Donny was a really bad dude,” Greg told me. “He was my dad’s sister’s husband. He used to call me the Cop Killer when I was a little kid. He hated cops because he was a criminal. He had me convinced that I’d killed a cop. I was terrified, because whenever a cop car came by, he’d pretend they were after me, and I would hide. When you’re a little kid and someone says you did something, you believe it. My parents would laugh about it and think it was funny. My mother would say, ‘Oh, don’t do that to him.’ But I was terrified. He always called me the Cop Killer, and I hated it.”

A short time after they returned from Florida, Greg’s family joined the beach club at Branford Harbor, and they spent every weekend at the shoreline, so he grew up always being near the ocean. They would often eat lunch at a restaurant overlooking Long Island Sound. One day he watched some fishermen in a boat just offshore, catching bluefish one after another. He was completely enthralled.

“My parents kept yelling at me to eat, but I just kept staring out the window, watching these guys fish,” said Greg. “I thought it was the greatest thing in the world, and I knew right then and there that I had to have my own boat someday.”

Greg had a hard time learning during his early years in elementary school. In addition to having dyslexia, which made reading difficult, he probably had obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, though the latter two conditions were not diagnosed at the time. He couldn’t concentrate at all on his work in class and constantly daydreamed—usually about fishing. Even just walking around school could present problems for him. For one thing, he always felt a powerful need to step up onto a curb or a staircase with his right foot first, so it stressed him whenever he was approaching them as he tried to estimate the distance in his mind and shorten or lengthen his stride so his right foot would be in the correct position to step up when he got there.

“It drove me crazy,” said Greg. “It was starting to get really noticeable, and I felt like I had to hide it from everybody.”

Greg’s dyslexia was diagnosed when he was in third grade, and he started taking special education classes to help him with his reading and math skills. The classes were useful, and he attended them for several years. He especially appreciated the efforts of Miss Flynn, one of the two special ed teachers at the school. All three of the boys she was working with—especially Greg—loved to go fishing, so she tried to incorporate fishing into their lessons so they would pay attention. (One of the other kids in the program was Scott Jackson, who became a lifelong friend of Greg’s.)

“The things we read and the math problems she gave us were almost always about fishing,” said Greg. “Like, ‘If you catch this many fish and you do this, how many fish will you have?’ It was great.”

The downside was that Greg and the other two boys were the only students in the entire school taking these classes, so it set them apart from their schoolmates. Everyone knew what was happening when G

reg would get called out of his regular class to go to special ed, and his classmates made fun of him. He became hyperaware of his disabilities, which gave him a sense of inadequacy in some areas of his day-to-day life.

But in fishing he knew he was absolutely capable—the most capable person around—and it became his escape from everything in his life that made him feel bad: his learning disabilities, his often testy relationship with his mother, and bullying by his classmates. At the edge of the water, his concentration was absolute as he closed his eyes and imagined the fish swimming underwater somewhere right before him. He was always trying to put himself into their minds, obsessively striving to understand everything about them. The rest of the world just melted away. He had found the essence of his being: to be a fisherman. Nothing else mattered.

GREG WAS somewhat of a nerd in elementary school, always doing his obsessive experiments—burning ants with a magnifying glass; collecting bugs; drawing underwater scenes of trout, bass, and other fish. It drove many of his teachers to distraction, except one.

“I remember one of my teachers, Mr. Mondillo, saw me drawing this beautiful freshwater fish scene when I was supposed to be working on a project,” said Greg.

“Wow, that’s pretty good,” said Mr. Mondillo.

“Thanks!”

“But that’s not what you’re supposed to be working on.”

“I know, but that’s all I can think about.”

“Well, I can understand that. I fish too.”

“Really?” Greg was amazed to find out he had a teacher who shared his interest in fishing.

Just a few days later, Greg was fishing at a nearby lake when he ran into Mr. Mondillo and another teacher fishing there. They weren’t catching anything, so Greg gave them a few pointers, and they caught a couple of pan fish. Then he asked them if they wanted to try fishing at a really great place, and they eagerly agreed. To reach the site, a pond on the far side of a farm, he took them a roundabout way, hiking on a muddy trail through the woods. He neglected to tell them it was private property and they were trespassing.

Born to Fish

Born to Fish