- Home

- Tim Gallagher

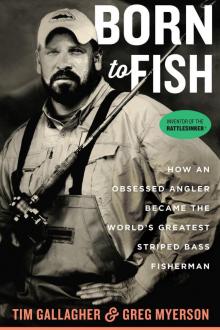

Born to Fish Page 17

Born to Fish Read online

Page 17

By the early 1990s, state game and fish agencies along the Atlantic Seaboard were patting themselves on the back for a job well done, as what looked like the most successful fish management program ever attempted produced a meteoric rise in striped bass numbers, and they opened up the fishery again to both sport and commercial fishing. Many conservationists feel strongly that the harvest numbers were increased prematurely—and their opinion appears to be borne out now as striped bass numbers once again plummet. What makes the situation more ominous than before is that we might not be able to bring them back this time. Striped bass face so many more problems now. They’re getting hit from all sides. The bays where they spawn and spend the first couple years of their lives are polluted and becoming increasingly eutrophic from an oversupply of nutrients, which causes explosive growth of algae and other plants and depletes the oxygen. Chesapeake Bay, the greatest striped bass nursery of all, now has vast dead zones caused by agricultural runoff from chicken and pig farms. These oxygen-deprived areas are killing not just crabs and small fish but numerous striped bass as well. The fish can’t live in these areas, so they’re forced into areas with warmer water, where the heat or a lack of food often kills them.

On top of everything else, the commercial fishing industry is still catching huge numbers of striped bass. In some ways, the harvesting of coastal game fish to sell is an anachronism whose time should be long past. The United States has a long history of exploiting wild animals for profit. In the nineteenth century, commercial hunters in the Northeast decimated deer, moose, and caribou populations to feed lumber camps, which led to the extinction of the caribou in Maine and New Brunswick. In addition, commercial waterfowl hunters up and down the Atlantic Coast went out in rowboats, using punt guns (almost like small cannons), sometimes shooting a hundred or more ducks in a single shot at night as the birds slept on the water. The federal government shut this kind of market hunting down a century ago, declaring that these mammal and bird species are game animals only and cannot be sold. But the coastal game fish were not included in this designation, so commercial harvesting of striped bass and other coastal fish continues in several states.

A persuasive case can certainly be made for declaring the striped bass a noncommercial game fish throughout its historic range on the East Coast. Unlike many commercial fish, which inhabit vast areas of open ocean, the striped bass is a coastal species and has a very limited range, so commercial fishing has a huge impact on them. Fortunately, the species has a large number of devoted allies—most of whom are sport fishermen—who hope to completely shut down the commercial fishing of striped bass.

It’s immediately clear as you talk to avid striped bass anglers like Greg how much they admire these fish. Although striped bass are magnificent hunters, they are not viewed as mindless killing machines the way sharks and bluefish often are. There’s something unique about a striped bass. Those who know it best say it has “personality.” This is exactly what got to Greg: seeing them eye to eye as he hauled them from the water, and feeling a sense of deep sorrow if he harmed them. This experience is what made him turn away from killing striped bass. And he’s not the only one. In my travels I’ve met dozens of people—scientists, conservationists, journalists, and just plain avid fishermen—who are thoroughly dedicated to saving the striped bass.

One such person is Dave Ross, an oceanographer, now retired, who spent the bulk of his career at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod. He is the author of numerous scientific and popular articles and several books, most recently The Fisherman’s Ocean. As a leading oceanographer, he has testified before Congress several times. You don’t have to talk with him for long to see how enraptured he is with the beauty and wonder of fish.

“To me, fish are without a doubt the neatest creatures we’ve got,” he said. “They’ve been around about 450 million years—that’s 200 million years longer than the dinosaurs—and they’ve evolved beautifully with their environment. Their sense of smell is about a million times better than ours. They live in the deepest part of the ocean, the shallowest, the coldest, and the saltiest. They are wonderful.”

But he reserves special praise for the striped bass. “A striper has an amazing ability to live in fresh water and salt water. Physiologically, to do that is just startling. And striped bass just seem different from other fish—more curious, more elegant.”

Ross has built his life around studying and pursuing striped bass with a rod and reel. “We live on Cape Cod, on the water,” he said. “I can basically hop into my boat and go out and fish for a couple of hours. If it’s not so good, I come home.”

When asked about the status of the striped bass population along the East Coast, he rushes to the defense of the fish. “Think about this: recreational fishermen are allowed to harvest one bass over twenty-eight inches per day,” he said. “Most bass over twenty-eight inches—maybe ninety percent—are females. And commercial fishermen are allowed to take a million pounds of fish over thirty-four inches in Massachusetts alone. Those are all breeding-age females. How can a management scheme like that work?”

Fisheries managers talk constantly about biomass—the total tonnage of fish in a fishery—but all too often they don’t look at the variety in the size, weight, and age represented in the striped bass population. You need to have the big breeders to have a healthy population. Another problem, according to many sport fishermen I interviewed, is that the fisheries managers reinstituted the striped bass harvest at what’s called a maximum sustainable yield (MSY)—a projection based on a rough estimate of the number of fish in the population. These numbers could easily be off by 50 percent or more, and yet the MSY is determined by these estimates.

Ross makes no bones about how wrongheaded fisheries policies are when it comes to the striped bass and the current allowable harvests in most states. “Harvest is a phony word,” he said. “People have their heads stuck in the sand; they just don’t want to acknowledge it. If you look at the statistics for the last ten years, the highs are getting lower and the lows are getting lower. And almost all of the fisheries committees are stacked with commercial fishermen.”

From 2006 to 2011, he points out, there was an 83 percent decline in the number of striped bass caught by recreational anglers, so the catch is definitely down. And the data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that the catch in 2011 was only 16 percent the size of the catch in 2006. He attributes much of this decline to the fact that so many large female bass are being killed off. “It’s no surprise that a fifty-pound bass would have more eggs than, say, a ten-pound bass,” he said. “But the eggs from those bigger fish are also far more viable. We’re harvesting the wrong size of fish and doing it badly. You can’t keep harvesting all of the big females. You’re killing off the most genetically desirable fish, the ones you need most in the breeding population.”

Dean Clark concurs with Ross about the decline in striped bass numbers. Now in his seventies, Clark is a former New York City adman, from the golden age of Madison Avenue in the 1960s. He is a staunch defender of the striped bass. “It’s like the 1970s all over again, there’s no question about it,” he said. “And now, anyone who says, ‘Look guys, we’re in trouble,’ is defined as a tree-hugging Chicken Little, screaming that the sky is falling, and is totally discredited. Well, I’m not a left-wing tree-hugger. I’m a right-wing conservative—but one with a vested interest in conserving the natural world.”

In the years-long struggle he and the others have been engaged in to save the striped bass, Clark compares himself to Don Quixote. “It’s an uphill battle. All of us are out here tilting at windmills every day. It sometimes feels like a fool’s errand in many regards, because the deck is stacked so hard against conservation.”

Like a good number of the sport fishermen I interviewed, Clark feels disdainful of the work of some fisheries biologists. “When a biologist says it’s a recovered fishery, what do they mean?” he asked. “In the late 1600s in New Engl

and, striped bass were so numerous that laws were passed forbidding you from feeding them to slaves and indentured servants more than five days a week.”

In those days, Clark points out, people were beach-seining striped bass—going a short distance from shore in a rowboat, encircling the entire school of fish in a long net, and using a team of horses to haul the catch up on shore. And the fish they caught were enormous, with an average size of more than fifty pounds. Now the average size of the striped bass caught by fishermen is less than twenty pounds.

“When you hear the phrase ‘a recovered fishery,’ and people are chest thumping, take a deep breath, and say, ‘Wait a minute: What do you really mean here?’ ” said Clark. “I remember back in the 1950s when it was very easy for anybody to go out and catch a twenty-five- to fifty-pound bass. Now, experienced fishermen go entire seasons without doing that.”

Clark heaps a good deal of the blame on the commercial fishing community and compares it with the market hunters who devastated wild game populations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He makes no bones about what he thinks should be done: “When a commercial fisherman turns up at a meeting and says, ‘Look, you can’t stop me from fishing for striped bass; my livelihood depends on it,’ it’s the same argument we heard from the market gunners in the 1920s. But back then, the managers had the guts to say: ‘I don’t care. Go pick up a hammer. Find another job.’ Today we have proven methodologies for getting people out of the fishing business in an empathetic way. We can buy them out. It was done thirty years ago with the salmon fishery in Canada.”

Like Ross and Clark, many of the anglers working tirelessly on behalf of the striped bass are the same people who fought to save the fish in the 1970s. People like Brad Burns of Maine, who helped push for the 1980s moratorium. Later, in 2003, he was one of the founders of Stripers Forever. At that time, commercial fishermen were pushing for a significantly increased catch quota in Rhode Island, and it looked like it would be approved. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, or ASMFC, had already passed a whopping 40 percent increase in the commercial fishing quota, so Burns and the others used it as a rallying cry. The Rhode Island Marine Fisheries Council, which was largely controlled by commercial fishing interests, had already approved the increase, and it needed only to be rubber-stamped by the governor. But Burns and other avid supporters of striped bass conservation stepped in and launched a grassroots campaign aimed at the governor. “We got people to write letters to the governor, attaching cancelled checks from fishing guide services they’d paid for, as well as credit card receipts for gasoline, restaurant meals, and hotels—all to show just how much money sport fishermen were bringing to the state,” he said. “The governor finally said, ‘This is crazy. We can’t do this. I’m getting all these letters from people and copies of checks!’ ”

A major part of the strategy with groups like Stripers Forever is to show how much sport fishing is adding to the economy. It’s a harder sell to make than that of the commercial fishermen who can point to the tonnage of fish they haul in and the amount of money their activities bring to the economy. But revenues from sport fishing are actually significantly higher than those from commercial fishing, and state governments need to be made more aware of this.

Now in his sixties, Burns has never stopped fighting for the striped bass. It’s probably safe to say that few people love this fish more than he does. His friend, the late angling author John Cole, wrote that he had once seen Burns kiss a big striped bass on the head before releasing it.

“I enjoy the spectacle of seeing a lot of striped bass—as many big ones as possible,” said Burns. “I love seeing them rolling around on the surface of the water, chasing baitfish up on the beach. To me, that’s what it’s all about—not about taking home a fish to eat.” He hasn’t killed a striped bass in years. If he doesn’t see many stripers when he takes his boat out, he doesn’t even try to fish for them. “I’d feel like I was beating up on them,” he said. “If there are only a few around, I don’t want to be sticking hooks into them. It just doesn’t make sense. It ruins it for me.”

Burns believes overharvesting is the single biggest issue in the fish’s decline. He says commercial striped bass fishing should grind to a halt as soon as possible. “If we don’t have enough fish so that some guy can go out and fish all night and keep a fish to take home to his family, we certainly don’t have enough to start selling them,” he said. “The biggest problem is the commercial fishery’s philosophy. You have to have a dead fish to sell it to somebody, so they are all about pushing for more fish.” He blames the reduction in the quality of the fishery in Maine to the ratcheting up of the commercial harvest in the 1990s.

“The Kennebec River was a world-class destination in the early 1990s,” said Burns. “The number of fish coming into the river was simply mind-boggling. But as soon as they started increasing those commercial fishing quotas south of us, we could see it begin to drop off. And by the early 2000s, it was just a shadow of what it had been.

“You don’t need to be a fish scientist to see what’s happening to the striped bass,” he said. “You can just go out on the water. They are no longer there.”

The strategy pursued by Brad Burns and other members of Stripers Forever is to go after the Atlantic Coast states one by one and convince their regulatory agencies to shut down commercial striped bass fishing in their waters. If they get enough of them on board, there will be fewer people representing commercial fishing interests on the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission.

“I want game fish interests to have a majority vote on the commission,” said Dean Clark. “Recreational anglers have a far better track record for stewardship of game animals.” He wants nothing less than for the striped bass to be the poster child for the near-shore saltwater environment. “That way, we will start managing the resource holistically. We’ll look out for the tiny killifish and sand lances and menhaden; the oxygen content of Chesapeake Bay; the PCPs in the Hudson River; because everything that happens to all of those other things will be felt most by the top of the food chain, which is the striped bass. It’s going to take a long time. I will not get to see it in my lifetime, but maybe my grandchildren will. If I can help to get us one step closer to a responsible management ethic, based on stewardship as opposed to exploitation, I feel I will have made a contribution.”

So far this chapter makes a strong case against the commercial fishing of striped bass, but what about sport fishing? Are recreational anglers without blame? The answer is no. As commercial fishermen proclaim at every opportunity, there are thousands more sport fishermen than commercial fishermen in America, they harvest more striped bass, and the ones they take are often the biggest fish. They have a point. Many people who run guided charter boats after stripers are firmly convinced that unless their sport-fishing clients can slaughter fish and take them home to brag about it, they will not pay money to go fishing. And nothing draws new customers like seeing big striped bass stacked like cordwood on a dock. This should be stopped.

Another thing that needs to end is the emphasis on taking large fish. Why must a striped bass be at least twenty-eight inches in length to be kept, when almost all of the fish that size or larger are already breeders? Why not institute a “slot limit” in which anglers can only keep fish in the twenty- to twenty-seven-inch size range? The salmon fishery on New Brunswick’s famed Miramichi River is a prime example of what can be accomplished. The provincial government shut down commercial salmon fishing there in the 1980s, and required recreational anglers to release any salmon larger than twenty-five inches in length; and for the last couple of years, the Miramichi has been a catch-and-release-only fishery. And yet sport anglers still flock there from around the world to take part in the excellent salmon fishing, substantially boosting the local economy.

This approach is common in other segments of sport fishing. Anglers spend a fortune to fly fish for bonefish in the shallow tidal flats of Florida and

the Caribbean, and they release all of them. The same with many of the people who pursue native trout: catch-and-release is the order of the day in the best places, and very few fish are killed. Even in the major largemouth bass tournaments taking place in freshwater lakes across the country, the fish are brought in, weighed, and released unharmed. And this is a multimillion-dollar business, with boats, fishing equipment, resorts, and more built around these pursuits. Somehow the striped bass fishery missed the boat. For the good of the striped bass, this needs to change.

Greg hopes to use the notoriety he gained from catching the world-record striped bass to help change people’s attitudes toward the killing of big fish. He has been actively promoting catch-and-release striped bass fishing for several years. Most recently, he cosponsored the Fishing Against Cancer Tournament out of Westbrook, Connecticut, in September 2017, which offered major cash prizes in several categories, with all of the profits donated to cancer survivors. And every fish caught had to be released unharmed. As Greg always tells people, “Those fish are far more valuable alive than dead.”

Born to Fish

Born to Fish